John Bowlby Attachment Theory

JOHN BOWLBY:

- British Child Psychiatrist & Psychoanalyst.

- First attachment theorist who described attachment as a “lasting psychological connectedness b/w humans”. He gave the famous theory known as “John Bowlby Attachment Theory”, which is discussed below.

- Believed that the earliest bonds formed by children with their caregivers have a tremendous impact that continues throughout life.

- According to him,the attachment tends to keep the infant close to the mother ultimately improving the child’s chances of survival.

☆ What is Attachment?

A strong & affectionate tie we have, with special people in our lives gives us pleasure whenever we interact with them and provides a sense of comfort in times of stress.

Through psychoanalytic and behaviorist perspective, feeding can be seen as a central context, where the care-giver and babies develop attachment.

☆ Attachment Theory

First relationship of a child is a love relationship that will have profound everlasting influence on an individual’s mental development.

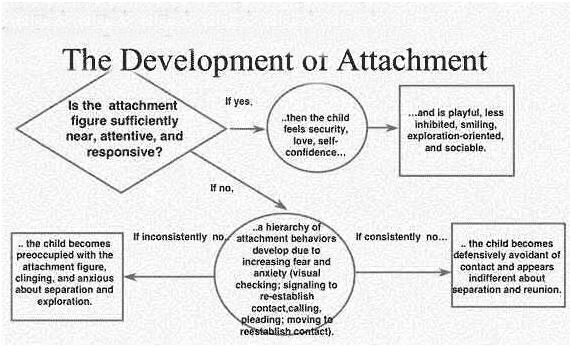

- Mothers (Caregivers) who are available and responsive, establish a sense of security in the infants such that they know that the caregiver is dependable, creating a secure base for the child to explore the world.

- Attachments must build a good foundation for being able to form other secure relationships.

☆ Components of Attachment

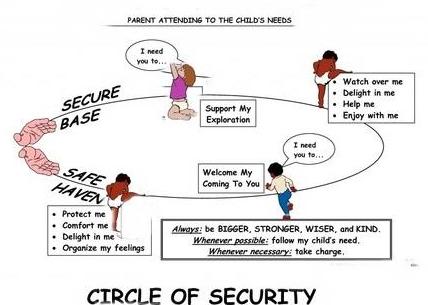

- Safe Haven: A child can return to the caregiver for comfort and soothing whenever the child feels threatened or afraid.

- Secure Base: A secure and dependable base is provided by the caretaker for the child to explore the world.

- Proximity Maintenance: The child strives to stay around the caregiver, which provides safety.

- Separation Distress: The child will become upset and distressed during the separation from the caretaker.

☆ BOWLBY’S ETHOLOGICAL THEORY

- Ethological Theory of Attachment recognizes infant’s emotional tie to the caregiver as an evolved response that promotes survival.

- John Bowlby induced this idea for infant-caregiver bond.

- He retained the psychoanalyst idea that the quality of attachment with the caregiver has profound implication for child’s security and capacity to form trustworthy relationship. He said ‘FEEDING IS NOT THE BASIS FOR ATTACHMENT’.

- The central theme of this theory is that the mothers who are available and responsive to their infant’s needs create a sense of security among their children. Knowing the dependability of the caretaker on them creates a secure base for the child to then explore the world.

Please note that the ages below are just in one of our groupings. However, attachments occur at ALL ages but the first attachments determine how the successive ones go! So when you are doing your attachments, you must show how they connected to your first attachment.

☆ 4 PHASES OF ATTACHMENT DEVELOPMENT

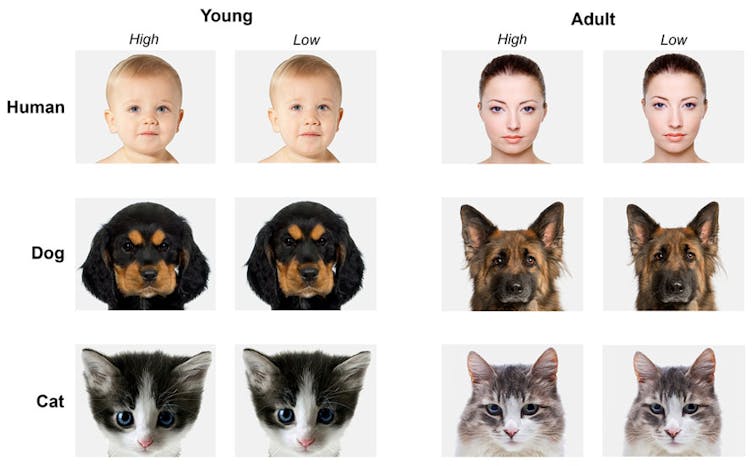

Babies are born with behaviors like crying, babbling and laughing to gain adult attention & on the other side, adults are biologically programmed to respond to their signals.

He viewed the first 3 years as the most sensitive period for the attachment.

According to Bowlby, following are the 4 phases of attachment:

- Pre attachment Phase (Birth – 6 Weeks)

- “Attachment in Making” Phase ( 6 Weeks – 6 to 8 Months)

- “Clear Cut” Attachment Phase ( 6-8 Months to 18 Months-2 Years)

- Formation Of Reciprocal Relationship (18 Months – 2 Years and on)

1. PRE ATTACHMENT PHASE (BIRTH -6 WEEKS)

- The innate signals attract the caregiver (grasping, gazing, crying, smiling while looking into the adult’s eyes).

- When the baby responds in a positive manner ,the caregivers remain close by.

- The infants get encouraged by the adults to remain close as it comforts them.

- Babies recognize the mother’s fragrance, voice and face.

- They are not yet attached to the mother and don’t mind being left with unfamiliar adults as they have no fear of strangers.

2. “ATTACHMENT IN MAKING” PHASE (6 Weeks – 6 to 8 Months)

- Infants responds differently to familiar caregivers than to strangers. The baby would smile more to the mother and babble to her and will become quiet more quickly, whenever picked by the mother.

- The infant learns that his/her actions affect the behavior of those around.

- They tend to develop a “Sense of Trust” where they expect the response of caregiver, when signalled.

- They do not protest when they get separated from the caregiver.

3. “CLEAR CUT” ATTACHMENT PHASE (6-8 Months to 18 Months -2 Years)

- The attachment to familiar caregiver becomes evident.

- Babies show “separation anxiety”, and get upset when an adult on whom they rely, leaves them.

- This anxiety increases b/w 6 -15 months, and its occurrence depends on the temperament and the context of the infant and the behavior of the adult.

- The child would show signs of distress, in case the mother leaves, but with the supportive and sensitive nature of the caretaker, this anxiety could be reduced.

4. FORMATION OF RECIPROCAL RELATIONSHIP (18 Months – 2 Years and on)

With rapid growth in representation and language by 2 years, the toddler is able to understand few factors that influence parent’s coming and going, and can predict their return. Thus leading to a decline in separation protests.

- The child can negotiate with the caregiver to alter his/her goals via requests and persuasions.

- Child depends less on the caregiver along with the age.

SOURCE: https://studiousguy.com/john-bowlby-attachment-theory/